How “Perfect” Pop Music Trains Us to Reject Difference

I was listening to the new Taylor Swift record The Life of a Showgirl and about 15 min into the record I thought to myself: “this sounds absolutely perfect.”

To my trained ears there is not a single deviation in tempo. The vocal performance is pitch perfect. Every articulation from the other instruments are exactly on time. I hear no variance between the bass and kick drum. The guitars, piano, and synth elements all sounds as if they were performed by the most consummate musicians to ever walk the earth.

But is it possible for human beings to perform music with such microscopic precision? Does it matter if the music we listen to is the actual reflections of embodied performances, or just mere representations of human like gestures?

I contend it matters profoundly. When we erase the subtle negotiations that make music human, we lose more than a fat pocket. We lose one of the last remaining symbolic forms that teaches us how to inhabit time together. And when we can no longer inhabit time together, we lose the very conditions for social life itself.

Let’s explore these stakes by taking a close look at the third song on Swift’s new record — Opalite.

After the chorus-drenched electric guitar intro, the vocal pickup comes in on the &-of-2 — “I had a bad habit” — with the drums and bass entering on beat one of the verse. Three beats in, my body screams: FLEETWOOD MAC.

I love Fleetwood Mac. One of my earliest memories is sitting in the living room of my childhood home, watching my mom and dad play backgammon while Dreams played on the record player. The album Rumours was released the year I was born, and so many of my earliest memories are saturated with their music. So when I hear the first few notes of the verse in Taylor Swift’s song, my body reacts.

After vibing out to this for four minutes, that perfection in Opalite really started to stand out. Being a former professional session drummer, I zero in on the drums. They sound real, but they’re quantized — locked to a grid. Every hit lands exactly where the software dictates, with no human variance.

Dreams, on the other hand, especially when Mick Fleetwood does a fill — and he does a lot of them, something you will not hear in a modern pop production — has an obvious push and pull to the groove.

So let’s do an analysis of the tempo in both songs.

The Tempo Maps

For this test I used Logic Pro, a professional DAW that can measure how the tempo of a song changes over time (among many many other tasks). I loaded each stereo mix into a track and had Logic run a tempo analysis. The software scans the audio waveform and identifies small timing shifts through transients. Once the analysis was complete, I converted those results into a tempo map, which is essentially a record of how the song’s groove behaves from start to finish.

I exported that tempo information into an Excel file (by copying and pasting the tempo changes from the list editor) and then ran some statistical analysis on it (thanks grad school). This process was repeated exactly the same way for both Taylor Swift’s Opalite and Fleetwood Mac’s Dreams, ensuring the results can be compared directly.

Full Tempo map for Taylor Swift’s Opalite

Bar Tempo Time

1 1 4 124.9988 00:00:11.78

31 4 4 125.0232 00:59:12.79

47 4 4 124.9896 01:30:05.68

63 4 4 124.9892 02:00:23.73

79 4 4 125.0069 02:31:16.78

95 4 4 125.0045 03:02:09.75

111 4 4 124.9916 03:33:02.72

119 4 4 125.0413 03:48:11.74

We can see Opalite has eight tempo transitions. However, looking closely at these results — 125.0232 to 124.9896 to 124.9892 to 125.0069 — it’s clear these tiny variations are not meaningful tempo changes. They reflect the limits of Logic’s tempo analysis algorithm, which can waver when it encounters non-percussive elements such as when the drums drop out for a section, or reverb tails on the vocals for instance.

Let’s look at Dreams by Fleetwood Mac:

Bar Tempo Time

1 4 1 120.6611 00:01:12.40

2 1 1 121.5177 00:01:24.75

4 1 1 120.9302 00:05:23.55

6 1 1 120.7445 00:09:22.73

7 1 1 122.7464 00:11:22.48

8 1 1 121.5279 00:13:21.39

9 1 1 120.3874 00:15:20.69

11 1 1 121.0033 00:19:20.43

13 1 1 120.6548 00:23:19.57

14 1 1 119.3633 00:25:19.35

15 1 1 120.7654 00:27:19.56

19 1 1 121.0417 00:35:18.35

23 1 1 120.7863 00:43:16.57

25 1 1 121.281 00:47:16.05

26 1 1 120.2429 00:49:15.43

27 1 1 122.7216 00:51:15.35

28 1 1 120.5096 00:53:14.26

29 1 1 121.5779 00:55:14.09

30 1 1 120.2624 00:57:13.37

32 1 1 120.1689 01:01:13.20

33 1 1 120.7047 01:03:13.14

35 1 1 119.5274 01:07:12.47

37 1 1 121.1891 01:11:12.79

39 1 1 120.2166 01:15:12.00

41 1 1 123.0874 01:19:11.66

42 1 1 120.5998 01:21:10.46

44 1 1 118.5136 01:25:10.06

45 1 1 120.8066 01:27:10.56

47 1 1 119.4816 01:31:10.03

49 1 1 120.0106 01:35:10.37

51 1 1 121.2491 01:39:10.37

52 1 1 120.0725 01:41:09.75

53 1 1 121.2312 01:43:09.73

54 1 1 119.2114 01:45:09.32

56 1 1 117.742 01:49:10.05

58 1 1 119.2509 01:53:11.79

59 1 1 117.5072 01:55:12.24

61 1 1 120.5563 01:59:14.34

62 1 1 119.2398 02:01:14.15

63 1 1 120.8421 02:03:14.41

64 1 1 119.1864 02:05:14.13

68 1 1 119.1744 02:13:15.42

69 1 1 120.2869 02:15:15.70

71 1 1 120.799 02:19:15.51

72 1 1 121.9705 02:21:15.24

73 1 1 120.675 02:23:14.40

74 1 1 119.6559 02:25:14.17

75 1 1 121.0503 02:27:14.29

76 1 1 119.6684 02:29:13.74

77 1 1 120.837 02:31:14.05

79 1 1 120.0982 02:35:13.30

83 1 1 119.4481 02:43:13.17

85 1 1 121.0745 02:47:13.54

86 1 1 119.9906 02:49:13.18

88 1 1 119.2077 02:53:13.19

89 1 1 122.0351 02:55:13.45

90 1 1 120.5418 02:57:12.59

92 1 1 119.799 03:01:12.23

93 1 1 121.5382 03:03:12.29

94 1 1 120.2944 03:05:11.59

96 1 1 119.2966 03:09:11.39

97 1 1 121.1713 03:11:11.63

97 3 1 127.4392 03:12:11.43

97 4 1 131.7173 03:12:23.25

98 1 1 119.1794 03:13:09.56

99 1 1 120.7629 03:15:10.04

101 1 1 122.1944 03:19:09.33

102 1 1 120.3158 03:21:08.41

103 1 1 121.5702 03:23:08.31

104 1 1 120.1696 03:25:07.59

108 1 1 120.526 03:33:07.36

109 1 1 122.9337 03:35:07.19

110 1 1 119.6162 03:37:06.04

112 1 1 119.1313 03:41:06.29

113 1 1 120.6459 03:43:06.58

115 1 1 119.2213 03:47:06.16

117 1 1 119.1054 03:51:06.68

118 1 1 120.9042 03:53:07.18

119 1 1 119.2645 03:55:06.68

120 1 1 120.3108 03:57:07.13

121 1 1 121.5587 03:59:07.02

122 1 1 119.8414 04:01:06.31

123 1 1 118.3286 04:03:06.36

124 1 1 119.4847 04:05:07.13

125 1 1 117.3247 04:07:07.30

126 1 1 120.1276 04:09:08.41

127 1 1 117.6927 04:11:08.37

Did you count all those transitions? There are 87 tempo transitions.

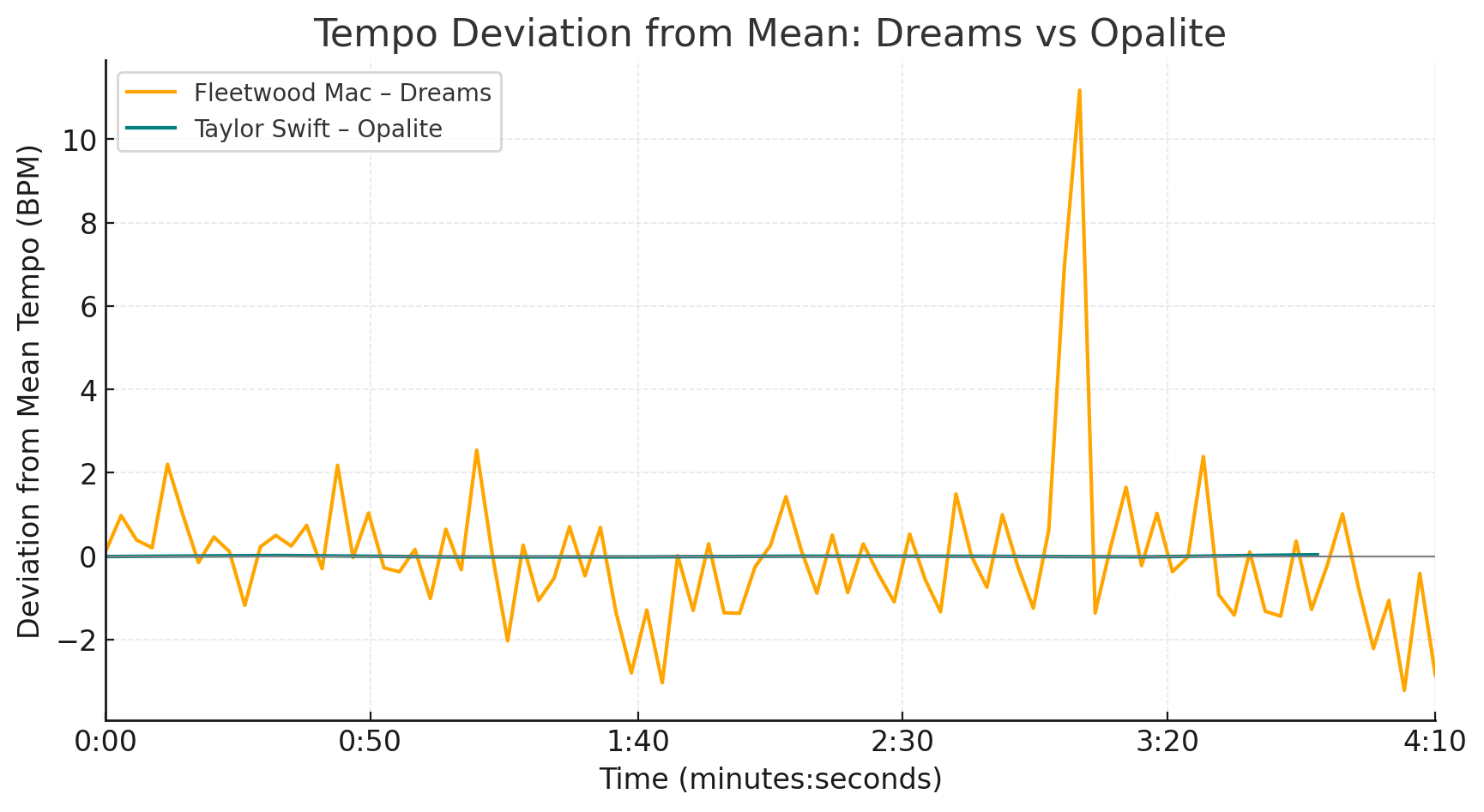

Next, I created a chart to show the normalized tempo deviation for each song. Normalizing the tempos allows their distinct absolute BPM values to be placed on a common scale (an apples-to-apples comparison). This makes the analysis more meaningful by revealing how each track moves around its own mean tempo, rather than focusing on their absolute tempo values.

This chart shows how each song’s tempo deviates from its own mean value over time, normalized so the two can be compared on the same scale. The large spike is when Mick Fleetwood does a 16th note fill in the outro chorus at 3:12 and he really does push the heck out of it. Give it a listen. That fill would never make it to a final mix today!

Be sure not to miss the flat green line. That is Opalite!

Before we get into why this matters, it helps to look at a few more numbers. Pay particular attention to the standard deviation and to how much of each song remains within 1 BPM of its mean tempo

Metric | Dreams | Opalite

Mean tempo | 120.54 BPM | 125.0 BPM

Standard deviation | 1.82 BPM | 0.02 BPM

Range | 117.32–131.72 BPM | 124.99 – 125.04 BPM

% within ± 1 BPM | 59.8 % | 100 %

So What

I imagine some may be saying — so what?

Taylor Swift’s song is perfectly locked to a grid and Fleetwood Mac’s song drifts all over the place. Maybe Swift’s audience prefers precision. Maybe this is just the sound of contemporary production. Maybe nobody cares about tempo variance except aging audiophiles clutching their brittle vinyl.

What’s the big deal if every single track on Opalite had been recorded in isolation, quantized to a grid and pieced together after the fact? From our current vantage point, you could even argue that Dreams just shows sloppy playing. The exact kind of imprecision that modern techniques have finally corrected. It’s called progress!

But this misses what’s actually at stake. The difference between Dreams and Opalite is not about aesthetic preference or reaching back to nostalgia. This is about two fundamentally incompatible answers to the question: What is music?

Opalite is a song in the sense that it has an intro, verse, chorus, bridge, along with a melody and some lyrics. And Dreams is a song in the same abstract sense. They both contain the agreed upon form for what constitutes a pop song.

But is a song just a combination of these formal elements absent a temporally constituted and historically embedded human being? Does a song exist outside of human embodiment?

This isn’t a trivial question. If music is simply the arrangement of formal elements — melody, harmony, rhythm, structure — then Opalite and Dreams are functionally equivalent. Both deliver the required components. Both can be notated and reproduced in their formal elements. Both fulfill the contract of what a pop song should contain.

But if music is something more than the sum of its isolable parts — if it’s a form of knowledge that carries epistemic weight comparable to formal logic or mathematics, but which arises through embodied coordination across time rather than abstract reasoning — then the perfect grid-lock of Opalite represents something categorically different from Dreams. Not better or worse in some subjective sense, but different in kind.

Susanne Langer: Presentational Symbolism

One of the most important philosophers of the 20th century is the American philosopher Susanne K. Langer. She is considered the first American woman to pursue an academic career in philosophy, and the focus of her work was on logic, mind, and the arts.

Langer developed a complete theory of knowledge that exists parallel to what she terms discursive knowledge — the domain of logic and mathematics, where meaning is constructed through sequential, propositional reasoning. But Langer argued that discursive knowledge cannot account for the full range of human understanding. And this insight crucial.

Art is not a by-product of feeling but a mode of cognition which objectively expresses forms of feeling for contemplation.

Langer calls these symbolic forms in art such as a song a presentational symbol. Unlike language, which conveys meaning sequentially through logical propositions, art presents its meaning all at once and can rationally hold contradictions within its form that sequential propositional statements can not. Its structure is not discursive but felt — what Langer calls “an idea of a feeling,” embodied in form. Music is the purest presentational symbol because it has no denotative function. A painting still references visible forms; poetry still uses words that carry semantic baggage from ordinary language. But music signifies nothing outside itself. It is pure form — temporal, relational, non-referential. Its meaning exists entirely in the lived unfolding of tension and resolution, which is why it can present “an idea of a feeling” without the distortion of translation. Music doesn’t represent the logic of sentience — it enacts it.

The Import of Expressive Form

In Langer’s seminal work Feeling and Form she called this symbolic form “the art symbol.” After its publication she decided to call it “expressive form” for a few reasons which will help us illuminate the distinction I am attempting to make between Opalite and Dreams.

The problem with “art symbol” was that it invited confusion with what Langer calls “genuine symbols” — the kind used in language, mathematics, and logic. Unlike mere signs, which indicate something (such as smoke for fire, or a noun for an object), genuine symbols operate within a formal system where meaning is defined by relations and can be translated or combined discursively. They point beyond themselves to something that can be stated.

But art doesn’t work this way. Art doesn’t refer to feeling the way a word refers to an object. It expresses an idea of feeling by presenting the form of felt experience directly, in a way that makes it perceivable and knowable. This is why Langer shifted to “expressive form.” The work of art is the presentation of feeling’s morphology. You don’t decode it. You experience it — and learn from that experience.

And this is where the term “import” becomes crucial to Langer’s argument. Distinguishing carefully between meaning and import, Langer shows that meaning is what genuine symbols have — fixed, translatable content that can be stated in other terms. Import, however, is what expressive forms have in the sense that a song “carries with it” a sense of vitality, emotional content, the feeling-tone of lived experience, what we call the morphology of lived life.

What is remarkable in Langer’s conception of expressive form is that it allows us to engage with art objectively and rationally — to understand it as symbol, not signal or symptom.

Art is not self-expression or emotional catharsis. It’s a vehicle for knowledge. As a presentational symbol, it formulates the elusive dimensions of affective experience, making them available for understanding. It is through this encounter with expressive forms that we learn from our own interior lives. We come to recognize patterns of feeling that resist discursive articulation and the artwork presents, in a single perceptual whole, what cannot be expressed sequentially in words.

Massumi’s Insights

The philosopher Brian Massumi, in his book Semblance and Event, extends Langer’s insight in a direction that clarifies what’s at stake in the gridification of music. Massumi argues that art and everyday perception exist in continuity with one another. We always perceive relationally and processually as life unfolds dynamically, and in constant flux, with multiple concurrent tensions and resolutions happening simultaneously. But this dynamic complexity usually recedes into the background of our awareness. We feel it implicitly, but we don’t attend to it.

Art, Massumi argues, is the technique that makes this implicitly felt vitality explicit:

In art, we see life dynamics ‘with and through’ actual form […] Art makes us see that we see this way. It is the technique of making vitality affect felt. Of making an explicit experience of what otherwise slips behind the flow of action and is only implicitly felt.

This is precisely what Langer means when she says art gives us access to the forms of feeling. Art foregrounds and objectifies what is already happening in our lived temporal experience, and places it in virtual from so that we can engage and learn from it. As Massumi says, “Art brings back out the fact that all form is a full-spectrum dynamic form of life. There is really no such thing as fixed form.”

So then what does any of this have to do with Opalite or Dreams?

If we take Langer’s work seriously, and I believe we should, she illustrates that music and art more generally, is another mode of knowledge production. It is a specific form of knowledge production that enables us to learn not what Taylor Swift or Fleetwood Mac feel, but what we feel. And, crucially, it is through this encounter with expressive form that we come to understand the patterns and structures of our own interior lives and how they fit, or don’t fit, with others in ways that discursive articulation cannot access.

The critical point here is that we learn this publicly. We gain knowledge of our interiority through shared symbolic forms such as music, painting, dance, and even architecture.

When those shared forms are systematically engineered toward mechanical perfection, both producers and consumers are being trained — often unconsciously — to expect a world without deviation. That is, to expect others to exist out of time and out of context, as mechanical representations of predictability rather than living participants in a shared temporal process. The more we internalize that expectation, the less patience (see violence) we have for the objectively rational, embodied rhythms of real human coordination.

Bringing the focus back to the gridification of music, this habit of hearing only flawless synchronization conditions us to experience other humans as sources of disagreement and delay. The aesthetic normalization of perfect time translates directly into diminished tolerance for the temporal and affective plurality on which democracy depends.

When I listen to Dreams, I’m not having a private revelation about my own feelings. I’m encountering a public object that presents the morphology of temporal experience — both its coordinated and uncoordinated moments — in a form available to anyone who listens. It is in this virtual space that we recognize, or fail to recognize, the structures of feeling that pattern our lived lives. Here we learn to attend to experiences we feel intuitively but cannot articulate discursively.

Music — as I have defined it here: presentational symbolism that objectifies subjective reality — is the weft that threads through society’s warp. It is the shared symbolic infrastructure through which mutual recognition becomes possible. Access to this shared interiority emerges through repeated encounters with expressive forms that objectify the patterns of lived experience. Those drum fills that cause Dreams to push and pull dozens of times throughout the piece — those are not imperfections, they are the objectified form of relational presence. The song presents tensions and resolutions as negotiated and embodied, not predetermined. The grid cannot hold this. It collapses the presentational symbol back into data.

This is what I mean by flattening — the reduction of multi-dimensional temporal experience to one-dimensional sequence. It’s why my handle on the website Medium is @WeWillNotBeFlattened.

Langer has this wonderful phrase:

The arts objectify subjective reality, and subjectify outward experience of nature.

This is the crux of the matter. Taylor Swift’s Opalite can not be an objectification of subjective reality because we are not robots existing in perfect clock time.

We are messy, comic-tragic humans who experience the world temporally within a plurality of concurrent, competing flows — an endless cascade of tensions and resolutions that can only be given objective symbolic form through the virtual image of music.

Langer states in chapter 7 of Feeling and Form — “The Image of Time”:

The clock — metaphysically a very problematical instrument — makes a special abstraction from temporal experience, namely time as pure sequence […] Conceived under this scheme, time is a one-dimensional continuum […] But the experience of time is anything but simple. It involves more properties than ‘length’ […] Life is always a dense fabric of concurrent tensions, and as each of them is a measure of time, the measurements themselves do not coincide. This causes our temporal experience to fall apart into incommensurate elements which cannot be all perceived together as clear forms.

The Political Stakes or My Response to — so what?

Almost two years ago during the Super Bowl halftime performance, Alicia Keys sat in during Usher’s set and when she began the song, the first 2 or 3 notes were a bit flat. You know, she is a human being, like you and me, and needed a few seconds to lock in during the chaos of a halftime show performance. Well guess what: within an hour of that performance, the NFL had someone autotune her voice so the official rebroadcast was “perfect.” They then went on a rampage to have all original versions of the “flub” removed from the internet. I wrote about this in a piece called ‘When Did We Lose the Right to Be Imperfect? — Alicia Keys’ Super Bowl Flub and Trump’s Exploitation of Meritocracy’s Discontent,’ before all the versions were removed from history.

Here is what remains of the clip I had in the article:

Screenshot from my Medium piece on Alicia Keys Super Bowl halftime performance. Article Link.

The tragedy of what is “not found” is not Alicia Keys’ flub. It is the loss of the weft itself: the expressive forms through which we objectify subjective reality and learn who we are as embodied, temporal beings. What the NFL removed — and what we’ve been trained to accept as inferior — is precisely the presentation of human coordination: messy, illogical in a discursive sense, wholly contingently alive, full of deviation and delay. What they replaced it with, and what pervades Opalite and Swift’s entire album The Life of a Showgirl, is inhuman machinic perfection. Not embodied experience made perceivable for contemplation, but embodied experience annihilated and replaced with algorithmically performed perfection. The grid doesn’t reflect us. It denies our validity.

The Mechanism, Not the Metaphor

I don’t think anyone will deny this claim: Things in America today are not going well. No matter which side of the political divide you are on.

I don’t need to spend 5,000 words outlining how our society, not just in America, is fraying — that we seem unable to understand each other, that a tenor of violence pervades almost every aspect of our daily lives. We feel it as we move through forms of human coordination that no longer coordinate. The rhythms of shared life — conversation, labor, the art we consume, where we place our attention — have become dissonant without resolution. What once formed a fabric of reciprocal attunement now feels jagged, syncopated, and unnaturally automated. We move beside one another, but not with one another.

The collapse is not just in the political, the economic, or familial realm. It is temporal. We no longer inhabit time together. Our collective sense of duration, the pulse through which meaning and relation are sustained, has been replaced by a series of atomized, discrete beats.

My main contention here is that gridified music is part of this collapse, and not a small part of it.

Yes, I am arguing that Taylor Swift, and almost every other major pop, rock, country, R&B, and rap artist producing music today is contributing to the conditions that put Donald Trump in the White House and sustain the rising violence and diminishing quality of life for nearly every American outside a few thousand families at the top.

You may say: you can’t seriously be arguing, Jeffrey, that using Pro Tools’ Beat Detective algorithm — quantizing every track, comping and piecing performances together through infinite undo capabilities — is contributing to our social malaise.

Actually, I’m not arguing it’s the reason. I’m arguing it’s a part of the mechanism — and I’d wager a larger part than most want to accept.

When music ceases to present the morphology of coordinated temporal experience — when it stops teaching us how to inhabit time together — we lose one of the primary symbolic forms through which mutual recognition becomes possible. And a society that cannot recognize shared patterns of feeling becomes vulnerable to those who exploit that vacuum.

Langer said in 1958:

Art education is the education of feeling, and a society that neglects it gives itself up to formless emotion. Bad art is corruption of feeling, This is a large factor in the irrationalism which dictators and demagogues exploit.

Do we have empirical evidence of my claims here? Not yet. There’s a need for social science research comparing how people coordinate and relate after listening to gridified versus non-gridified music. That research would be invaluable. I can envision organizations like More in Common or The Aspen Institute — think tanks that look at ways to promote healthy democratic societies — funding such a study.

But if we take Langer’s insights to their logical conclusion — that art objectifies subjective reality, that it educates feeling, that bad art corrupts feeling and renders populations vulnerable to irrationalism — then the systematic elimination of embodied coordination from music must have social consequences. We are being trained, track by track, to accept algorithmic perfection as normal and to perceive organic human adjustment as failure. That training doesn’t stop at the boundaries of music. It shapes how we understand coordination itself — in conversation, in labor, in democratic life.

In our hyper-connected, digitally distributed world, where music saturates nearly every waking moment, this transformation cannot be neutral. If the primary symbolic form through which we learn to recognize the patterns of shared temporal experience has been systematically corrupted, we should expect — and we are seeing — a collapse in our capacity for mutual recognition.

Gridification is not a metaphor, it is a mechanism of our social collapse.

A quick note on dance music: I do not consider dance music subject to my gridification critique. The distinction is structural. Dance music is composed through the grid with the understanding that it exists as raw material and not yet a complete presentational symbol. It achieves symbolic completion only in performance, when a DJ, temporally and situationally embedded within a specific venue, manipulates tempo, pitch, and sequencing in real time. The track as produced is not the final work; it is a provisional form awaiting its final articulation through embodied, relational presence. The DJ is not reproducing the work; they constitute the presentational symbol in that moment, for that room.